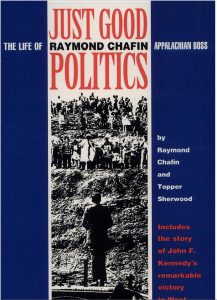

By Raymond Chafin and Topper Sherwood

My Preface to the book, published by the University of Pittsburgh Press in 1994.

I hesitated when Raymond Chafin first approached me with the idea of writing his autobiography. At least one local newspaper routinely identified him as a “Logan County political boss,” which constituted not one, but two strikes against him. People like me, in the more urban parts of West Virginia, often look down their noses at Logan County, much in the same way that cosmopolitan America often appraises West Virginia itself.

Logan, along with the other Southern coal counties – Mingo, McDowell, Wyoming, Boone, and Mercer – has long been shrouded by a dark history, known as one of those mountainous territories where coal miners scrape out dirty and difficult lives, where people live in hillside cabins, and where “politics” means “kin.” Most stories about Logan carried in Charleston newspapers are negative; they deal with poverty, violence, mining accidents, and, not least, political corruption. These are the images that first came to mind when I anticipated having dinner with Logan County’s leading “political boss.” By the same token, these stories – combined with my own label, “Charleston journalist” – likely did little to inspire Chafin’s confidence in me.

From that first meeting, Raymond Chafin surprised me by not conforming to my idea of the stereotypical Appalachian politician. I had expected a white-collar political broker/financier, adept at all the tricks and chicanery that journalists often wonder about but rarely describe in print. Instead I was introduced to a congenial man whose faded blue shirt had a tiny cigarette burns in it. Chafin didn’t give the impression of someone who made a lot of money in his life – from politics or anything else – and he answered all my questions with disarming candor. He struck me less like a political power broker than a bricklayer come straight from the job site.

Indeed, as I came to know him better, I learned that construction work has actually been Raymond Chafin’s primary source of income during his entire political career. Although power can itself be a bargaining chip, he wielded at least as much political clout by being able to produce roads, bridges, dams, and schools for Logan County. He also built a constituency of voters who have supported, more often than not, “his” candidates over a generation of election days. In a back-handed defense of machine politics, Theodore Roosevelt once said that the successful political boss “is very apt to be a man who, in addition to committing wickedness in his own interest, also does look after the interests of others,” and that any boss who acts only for himself “would probably last but a short time in any community.” The people who greet Raymond Chafin on the street every day seem, in any case, to be satisfied with his work.

“I never wanted much for myself,” he says with a wink. “I just like to win ’em.”

During my conversations with Chafin, I was eager – as most readers will be – to hear about the historic West Virginia primary campaign of 1960. It was, after all, John F. Kennedy’s hard-won victory there that caused his strongest democratic rival, Hubert H. Humphrey, to withdraw from the race, clinching Kennedy’s nomination for president. Ever since the last vote was tallied that spring, analysts have speculated about the effects of vote-buying and “out-of-state wealth” on JFK’s victory. Investigations were carried out by the US Justice Department, the FBI, anti-Kennedy Democrats, the Wall Street Journal, local newspapers, and Washington exposeur Jack Anderson. Invariably the conclusion was, as one former state governor declared (intending no apparent irony), that Kennedy had “sold himself” to the voters, not bought them.1

Still, the issue will not die. In a New York Times article in 1992, West Virginia novelist Denise Giardina wrote that the Kennedy campaign “overwhelmed Hubert Humphrey in West Virginia by putting large sums of money in the pockets of local officials.” Her Unquiet Earth, in fact, fictionalizes Chafin’s own legendary misunderstanding with Kennedy financiers, a story told in these pages.2

But Just Good Politics doesn’t merely satisfy one’s curiosity about the 1960 campaign. Just as fulfilling is Chafin’s description of a political culture that has endured in southern West Virginia for some time. Certainly many politicians have tried to tell their stories; others have had their stories told through prosecutors and grand juries. None, however, can offer with Chafin’s color or candor the behind-the-scenes deals, the polling-place maneuverings, and, perhaps most importantly, the political influence of larger bureaucratic interests on elections in this region.

Readers will quickly discern that Raymond Chafin describes a world that is not in line with the shining democratic principles they learned in school or those offered by the ponderous pundits trotted onto the screen each election day. Chafin describes deal-making, rigged elections, and votes bought with cash and whiskey. He tells us about men who were shot for siding with the wrong people in the wrong district during the wrong election. For all his cynical realism, however, we can trace most of the political practices described in this book to institutions likely to have been familiar to our country’s early voters.

Identifiable elements in the political culture of Southern West Virginia, in fact, date back to the days before the American Revolution, to the British Colony of Virginia. The high-born gentlemen of the Old Dominion were trading votes for pints long before any “moonshiners” appeared in Appalachia. Magisterial representatives were routinely chosen by the most wealthy landowners. Candidates were still forced, however, to compete for support, and many a gentleman won his laurels only after defying election laws and treating his voting neighbors to a drink. George Washington and another candidate reportedly gave Alexandria’s populace “a Hogshead of Toddy” on election day in 1774.3

Aristocratic Virginians later developed what historian John Alexander Williams calls a tradition of “oral political culture,” defined as politicians “traveling from place to place, making speeches and developing supporters on a face-to-face, friends-and-neighbors basis.4 Successful candidates attracted followers with personal friendship and favors. Like some formal Virginia institutions, the oral tradition persisted in West Virginia—especially in the Southern counties—long after the new state was established in 1863. Political patronage, similarly, remains familiar to most modern-day voters in both Virginias and elsewhere.

Virginia’s nineteenth-century political institutions also included a “court day,” the day on which the circuit judge came to a particular county to hold trials. Occurring several times a year, court day became as much a social institution as a political one, according to Williams:

Many people watched the trials as a form of entertainment, but others came to visit, gossip or shop. The county militia…usually held its drills on court day; young men competed in foot races and other athletics.There were shooting matches…. It was an occasion for people to visit their friends and relatives from other parts of the county.5

What was true for court day became true for election day, which historian Altina Waller calls “the most important social event of the year.” In the late nineteenth century, election-day politicians faced off against supporters and hecklers alike, and voters cast their votes aloud, publicly: “Everyone in the community was fully aware, not only of everyone else’s political beliefs, but of their status as landowners or tenants and their family connections. Men came to the elections prepared to state and defend their politics as well as their reputations, if necessary.”6 Such an environment insured not only that people and politicians met, literally, on common ground but that elections retained a free-for-all, hand-to-hand quality—not the media events they have become in most parts of the country today.

Raymond Chafin describes Logan County elections in much the same terms. He remembers when political candidates “came out to where you lived. They found you in your cornfield and told you what they stood for.” His family and friends “stuck together [and] voted together. And that,” he says, “made them powerful.” Chafin’s “Pony Express” meetings (described in chapter 6), the role of political patronage, and the use of slates all date back to a time when politics demanded more from voters— and perhaps offered more—than present-day iterative polling and tabulation. The political terminology is the same, but the impersonalized electronic networks that dominate the electoral process today are far removed from the political traditions of court day.

Face-to-face politics, on the other hand, can also be as far removed from the democratic ideal as they are from the media marketeering of today. Waller reminds us that many of the “clan feud” battles occurred at the polling place; Chafin tells how “dangerous” local politics could be, and he recounts the election-day murder of his own father-in-law.

“If you didn’t go out there and risk getting shot or killed,” he reminds us, “you didn’t work an election at all.”

One can only imagine the musings of John F. Kennedy as he entered West Virginia’s active political culture. We cannot know, of course, what Kennedy thought as he approached the 1960 primary. We do know that he had been reading up on West Virginia history and that he continued to be interested in the subject during the campaign. That April, Kennedy was scanning a map of the Mountain State while flying to Charleston on his private plane—shortly before meeting Chafin for the first time. (It is ironic, perhaps, that the leader of the first national media campaign would soon find himself immersed in the old-fashioned politics of Raymond Chafin.) Kennedy interrogated his companion, U.S. Congressman Ken Hechler, with questions about the state’s history.

“Tell me about the Indians,” Kennedy asked Hechler, letting his finger wander across Mingo and Logan counties. The West Virginia congressman offered what he could, but was amazed to realize that the Massachusetts Senator knew more than he did about West Virginia’s bloody frontier war.

“The Iroquois Confederacy produced great characters,” Kennedy commented. He ticked off the names of several Indian leaders, including Logan, an eloquent Mingo speaker who negotiated treaties for the Iroquois. Logan’s entire family was killed by white settlers in April 1774. Kennedy gazed out the airplane window and quoted the leader’s most famous speech, condemning the men who had betrayed his trust: “Who is left to mourn for Logan? Not one.”

There are indeed few left to mourn for today’s Logan, a county condemned as “backward” by generations of urban journalists. Raymond Chafin tells something of Logan’s story in these pages. Some will read it as a series of funny or clever anecdotes – “Br’er Rabbit” tales told by a wizened mountaineer from the strip-mined hillside that was once his grandparents’ homestead. Just Good Politics, however, offers more than that. It is a genuine bridge between our increasingly homogenized American society and a largely unexamined part of rural mountain life. Like so many other cultures, West Virginia’s traditional political culture may have something to teach us, even as it disappears with progress and the passage of time.

Topper Sherwood

,

Charleston, West Virginia,

1993

Footnotes

1. Dan B. Fleming, Jr., Kennedy vs. Humphrey, 1960: The Pivotal Battle for the Democratic Presidential Nomination (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co, Inc., 1992), p. 145.

2. New York Times, 31 October 1992, sec. 1, p. 21, col. 2; Denise Giardina, The Unquiet Earth (New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 1992). Also of interest are Giardina’s Good King Harry (New York: Harper & Row, 1984) and Storming Heaven (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987).

3. Edward N. Saveth, Understanding the American Past (Boston, Mass.: Little Brown & Co., 1954), p. 91.

4. John Alexander Williams, West Virginia: A History for Beginners (Charleston, W. Va.: Appalachian Editions, 1993), p. 111.

6. Altina Waller, Feud: Hatfields, McCoys, and Social Change in Appalachia, 1860-1900 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), p 16.